Constable and Turner

A clash of values at Tate Britain

Constable & Turner

A clash of values at Tate Britain

At Tate Britain until 12th April, two incompatible ideas of landscape painting are irresistibly opposed. Joseph Turner and John Constable—for some the two greatest British painters—hang side by side in a blockbuster so obvious you wonder why they don’t do it every year. John Constable was a visionary observer of the English landscape, the child of Tory landowners who returned with sacramental regularity to seek the “inner meaning” of his beloved Suffolk countryside. Joseph Mallord William Turner was a prodigy of light and colour, a self-made phenomenon who travelled Europe seeking out the extremes of visual experience. I changed my mind about who was greater, or truer, and which of those values mattered more, in every successive room.

Born within a year of each other, the two men lived through enclosure, reform, the dawn of industrialisation. They were the first generation of ‘landscape painters’ to understand that their subject could, and perhaps would, disappear. Perhaps that is why they worked with such urgency, making plein-air sketches and colour plans that modern viewers naturally compare with later artists. But this was a time when respectable opinion still demanded respectable art. The Royal Academy’s summer exhibition cast a long shadow across both men’s lives, and contemporaries quickly identified them as natural rivals. If Turner was fire, Constable was rain; if Constable was truth, Turner was poetry. Once, they were hanging side by side when Turner amended his canvas with a last-minute stroke of crimson. “He has been here and fired a gun”, Constable said.

John Constable, Dedham Vale. 1828. Oil on canvas.

I am naturally drawn to the paintings of John Constable, and Dedham Vale (1828), gives a good idea of why. It is a view of a flat valley under half-overcast skies. The road is dirty, the foreground brambles thickly observed. The river meadow is accreted from horizontal strokes of pale straw, lichen, brown and white. Light does not seem to fall in this painting. Rather, it is the changing outcome of every surface we see, widely broadcast throughout the tall, disordered cloudscape.

Like many of Constable’s paintings, this feels incredibly true to life. There is a sense that truthfulness involves owning up to what is disappointing in life. (Changeable weather. The flatness of the meadow. Those dull terracotta roofs.) For decades critics have discussed the tension between this objectivity and Constable’s interests as a Tory landowner, committed to a hierarchical vision of rural life. Perhaps these perspectives are more complementary than they appear. Is the quality of Constable’s realism not what accommodates political discussion in the first place? Dedham Vale is a space in history, subject to rain, law and ownership. To cross it would require a few hours and good boots. When you look at it, you understand that ‘landscape’ involves ‘land’—something more than the eye can hold.

J M W Turner, Crossing the Brook. 1815. Oil on canvas.

Hanging nearby is Turner’s Crossing the Brook (1815). Two women are fording a dark stream above an Italianate vision of Devon’s Tamar valley. Both pictures have absorbed the structural habits of Claude Lorrain: the downstage chiaroscuro, the framing tree, the sudden dip that abridges foreground and middle distance. But next to Constable, Turner looked much too sleek. His scenery felt vapid, mere occasion for a Picturesque fetish of distance and mist. One disadvantage of the rumble-in-the-jungle format is that rival artists don’t necessarily show to mutual advantage. I found myself gravitating towards the water with its palette of rust and black. Turner captures the clear-reflective surface shuttling back and forth between those states. Between the figures, a jumbled sheaf of brushstrokes ripples the surface of the painting itself.

A young prodigy, Turner was painting Italian landscapes long before he left England. What difference did it make seeing the real thing? Here Aeneas and the Sibyl, Lake Avernus (1798) is hung next The Bay of Baiae with Apollo and the Sibyll (1823), which was painted after actually visiting Italy. In the later painting, the blue that would read as clarity in England is understood as an accumulation of high, thin haze. The horizon pales with heat mist, not banks of cumulus. The landscape is not so automatically green, nor does the water contain an instinctive foreshadowing of cloud. The display seems to confirm the charge of invention—‘poetry’— that Constable’s paintings level at Turner’s. Yet both paintings are the products of deep observation, even if only one was observed in the right place.

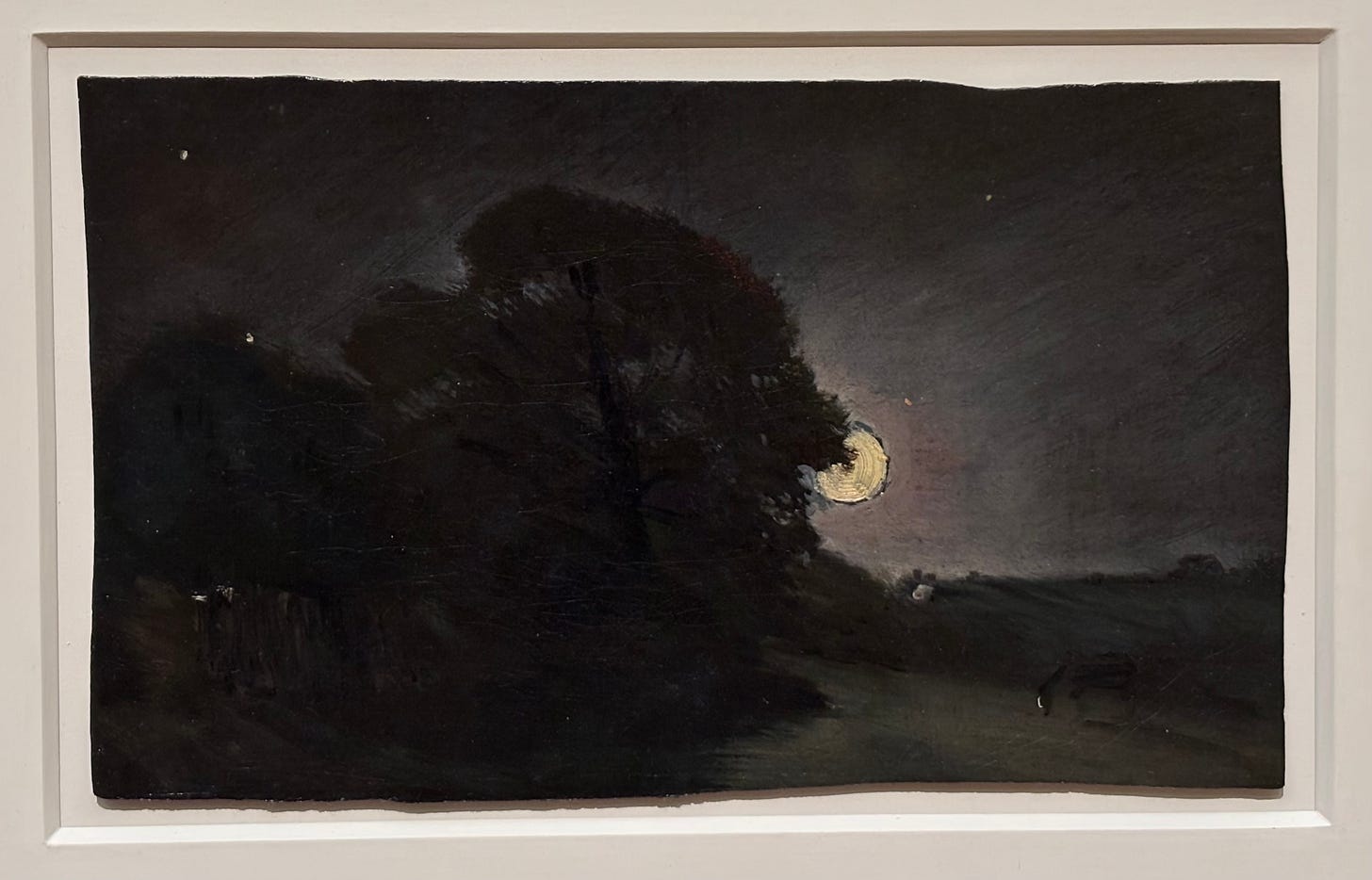

John Constable, The Edge of a heath by Moonlight. c. 1810. Oil on paper, laid on canvas.

Both painters produced studies that are now exhibited alongside finished works, and which challenge us to see them without imposing anachronistic passions. In 1815, Constable started bringing oils outside to note down the summer colours before his winter studio campaign. Here a buttery path drifts through shadowed green verges, and a pearly button of moon hangs inside a faint lilac aureole. It’s tempting to call this forward-looking, but it is the precision of the colours, not the freedom of the mark in itself, that’s so enrapturing.

Turner liked to build his pictures from pure colour studies, and there is no way around the fact that these are ravishing. I stood for a long time in front of Study for ‘Landscape: Composition of Tivoli’ (c.1817), writing the names of later artists in my notebook (Monet, Matisse, Rothko...). What Turner’s study looks forward to, though, is a finished composition. Contemporaries often described his almost magical ability to elaborate subject matter from his chaotic preparatory work. You can actually see it here in the shimmer of the water, the blue hills gathering themselves in the background. If you turn ninety degrees to look at Hannibal Crossing the Alps (1812), and see how little it might need to make a grand history painting.

J. M. W. Turner, Study for ‘Landscape: Composition of Tivoli’. c.1817. Pencil and watercolour on white wove paper.

The great surprise for me, in this show, was how disconnected I felt from the late Constables. I suspect the curators’ choice to paint the walls a rich, almost purple brown didn’t help. In Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (1831), for instance, my eye wouldn’t accept the prestige-Netflix grey of the building’s stone, never mind the rainbow. The painter began to turn his back on the unspectacular domain he had made his own. In Sketch for Hadleigh Castle (1828-9), a ruin stands in the foreground, its tower cracked open, with heavenly shafts of light falling beyond. I searched its scorched expanse for the resonant objectivity he once gave to forgettable Sussex afternoons.

John Constable, Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, 1828-9.

Turned lived on, working with the extremity that often comes upon painters in age. In the final rooms of the show hang the fiery and, yes, impressionistic scenes that made Turner the in-house radical of British art. Unsociable, eccentric, heavily addicted to snuff, he seemed to work harder and harder, undertaking long journeys to Switzerland and Italy. In his watercolour study The Bay of Uri on Lake Lucerne, from Brunnen (c. 1841-2), each layer of paint presents new information about how the lake’s surface receives the scenery. On the peaks behind, misty colours hesitate at the precise point where they might resolve into visible rock. The boatman holds his oar above the lake. Soon, I think, a paper moon will rise in the paper sky.

J. M. W. Turner, The Bay of Uri on Lake Lucerne, from Brunnen, c. 1841-2. Watercolour on paper.