The lord of limits

On Vermeer

We want to get closer to Vermeer. We see his immaculate canvases and we want to be closer to their crystalline shimmer of glamour and tenderness. In the sphere of mass image, Vermeer has a small church and its liturgy is detail: a skein of milk, a filament of lace or reflective metal, a pearl earring.

Yet it also seems important to us that there remains some distance between the painter and ourselves. We want his paintings to contain enigmas, codes, hidden stories. As with Shakespeare, the uncertainties of Vermeer’s well-documented life are magnified and overstated. His excellent reputation in his own lifetime is underplayed, as is his rediscovery in the nineteenth century. Discussion of his working method is often reduced to the unknowable question of what role the camera obscura played, if any, in his work. It’s not enough for Vermeer to be a miracle: we want to elevate him to the higher status of mystery, to create a space between us and him that is large enough to contain our aesthetics of longing.

At the Rijksmuseum, where a significant majority of his existing canvases are currently on display, each painting is fronted by a semi-circular ring to which hordes of visitors crowd, leaning in to descry a single visible brushstroke or unriddle the illusionistic purity of an impasto highlight. These barriers play with that conflicting sense of distance: come this far, but no further. On the outside walls of the museum hang microscopic sections from his paintings blown up thirty feet high and hung as ad banners, and they similarly seem to suggest that no matter how close you get, you’ll never be close enough.

A view of the Rijksmuseum.

These faintly pornographic mega-details indicate some of the contradictions that emanate from the name of Johannes Vermeer, the globally revered domestic miniaturist, the minimally productive, small-scale artist made famous by mass-reproduction and celebrated on a titanic scale—the notably silent painter who is currently making more noise than any other artist in the world.

The Rijksmuseum show is, before anything else, a masterpiece of theatrical exhibition design. Presenting Vermeer alongside none of his contemporaries, often placing just one small canvas in a room, the curators reify and re-canonise the painter in a category of one. Of the thirty-seven-odd known paintings by the mid seventeenth-century Delft painter, twenty eight have been gathered in Amsterdam for the next few months. This feat of organisation will likely never be repeated, and the mononymic exhibition title, ‘Vermeer’, is as authoritative and final as a full stop. Here it is then, your last chance to see them all before the Rijks is reclaimed by the esurient Dutch sea.

And he is a miracle, the subject of this exhibition. The painter who emerges over the course of these ten or so rooms is an obsessive, ingenious, highly intellectual artist: a worshipful student of the orthogonal, an inquiring master of optics and above all else, an extraordinarily sophisticated theorist-cum-theologian of painterly representation.

Of course there is that light, though to call it by the one name seems ridiculous. Vermeer’s light is always Vermeer’s in its microscopic operations, but its character and quality are entirely different in every scene. What shines down as something sensuous and enveloping in Lady With a Necklace is spare and holy in The Milkmaid, an elegiac dazzle in View of Delft, and full of plain-speaking disclosures in The Little Street. Vermeer’s light appears as a completely different phenomenon in each painting: beyond that constantly recurring left hand window we might as well be on different planets.

Vermeer spent almost the whole of his working life in Delft, and a view of the city is the first thing you see when you enter the show. It is intensely moving. Who made this glittering world, you wonder: the veiled blue-grey of its broad river, the travelling clouds, their cotton fringes and rainy undertows, this gemutlich strip of accreted stone and brickwork, these houses pecked with windows, arches, views, these distant rooves and spires, this right-angled imposition of order threatened by burgeoning foliage?

The abundance of natural scenery in the picture makes it unique in Vermeer’s surviving corpus. The picture is large for Vermeer, and the sandpaper sparkle of the town is set in a rather narrow strip between the expansive heavens above and the water below. God’s first creation, the fiat lux of Genesis 1:3, is shining with one mind on the divinely distinguished and enumerated world that came afterwards.

View of Delft. Oil on canvas, c. 1660-61.

The town though, is what draws your eye when you stand it front of it. Here is the early bourgeoise world: its scuffed decay, its differentiated materiality, its bright, opaque concerns of travel and business, its marine filigree, fine strips of mortar and architectural bobbles. Standing in front of it I felt almost hustled, my attention drifting helplessly back to this strip of human habitation. Sometimes Vermeer reminds me of a pickpocket, so reliably does he draw us towards his work, framing up our attention just the way he wants it so he can slip something else past us.

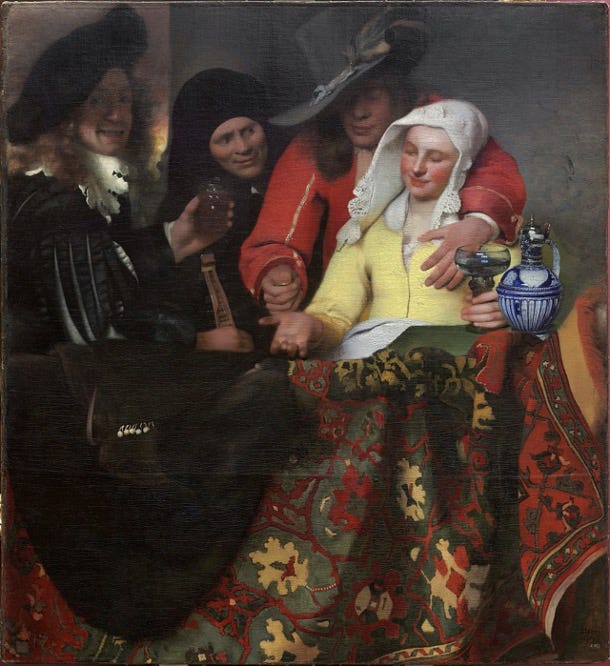

In the early history paintings, bafflingly unlike what followed, he seems to be wrestling with the question of what sort of artist he will be. He worked at a time of specialists and local tastes. Rembrandt and Hals made rough, expressive portraits in Haarlem and nearby Amsterdam; for a naval painting, you might go to William Van de Velde in the same city. In Utrecht, a school of Caravaggisti specialised in religious and biblical scenes. In Dordrecht and Leiden, your chief genre men were Jan Steen and Nicolas Maes respectively. In Vermeer’s hometown of Delft, tastes favoured restraint and elegance, so who knows what he was thinking when he painted this:

The Procuress. Oil on canvas, 1656.

‘Look up!’ says this painting, called The Procuress. ‘There’s nothing going on below the belt.’ The figure who looks out at the viewer with a grinning underbite is supposed to be a self-portrait: Vermeer himself, laughing at our impropriety in even viewing such a picture. The patron is groping the procuress as he pays, and beside her breast, a blue and white ceramic water jug puns indelicately on the encounter. Her extended, open palm is the very centre of the painting, and above it floats the coin that will pay for the encounter: an evocative, slim crescent of light. It draws the eye, tantalises the viewer. And no wonder: it is the inverted smile of the grinning man who is supposed to represent Vermeer. It is the admission of himself as a bought and sold commodity, a man who, in the final analysis, ranks below his client. With an empty palm, a leering grin and its curious inversion as a piece of silver, Vermeer satirises the oxymorons of displayed taste and public propriety that haunt the golden age of Dutch art.

The other history and religious paintings are a mixed bunch. In Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, the painter seems to have struggled with his attempt to extend the room space behind the two main figures, which dissolves into a chestnut and shit-coloured raft of semi-impossible right angles. Diana and her Nymphs makes no impression – in a room of other paintings you would pass it straight by. The most exciting work here is the seemingly impossible, surely-not-by-Vermeer, pseudo-mannerist Saint Praxedis, which one would call a fake were it not signed, dated and scientifically verified, apparently, as legitimate. The attribution is disputed; I was convinced of its quality, if not Vermeer’s authorship, by the material metronome of martyr’s blood, squeezed from a cloth, which this painting uses to keep time.

Then, at some time in the late 1650s, Vermeer found his vocation.

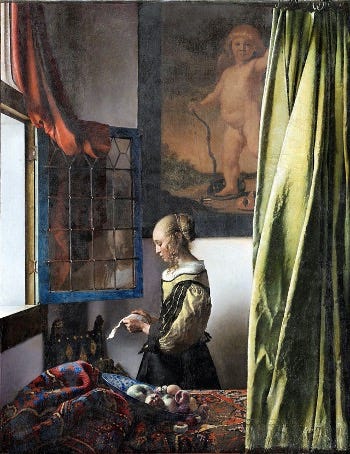

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Oil on canvas, c. 1657-1659.

The scene is always the same. A domestic interior featuring one or two figures. On the left is a window with light pouring in. On the back wall are nails, maps, mirrors or paintings. There are a few very distinct and separate objects in the room: a foot stove, a few chairs, a table, a basket, books, as well as carefully placed highlight points like jewels, chair studs or polished wood. Most importantly, there is some object of momentary attention or inattention around which the human drama, such as it is, converges: an instrument, a letter, a piece of thread, a metal balance, a mirror. When one considers the breadth of subjects and scenes available to a painter, it is a tiny vocabulary. Yet Vermeer didn’t strike me as a minimalist so much as what you might call an atomist. He is not interested in the freedoms that can be found in these limitations, or in the mysteries of process itself. The limited world of his mature paintings is the setting for a project of observation and differentiation, a non-exhaustive project since its premise is that the possibilities existing within these parameters cannot be exhausted.

The Love Letter. Oil on canvas, c. 1669-70.

I say ‘the human drama’, but it is an approximate phrase. What, in fact, is the moment that Vermeer paints? Photographers talk about a kind of shot they call a ‘caught moment’, something brief and otherwise unnoticed that has a pathos and beauty of its own. I think this gets us towards what Vermeer is interested in, which is what you might call the pose between poses. Whether attentively engrossed or suddenly distracted, the people in Vermeer are rarely being themselves, performing themselves, holding the postures of their personality. They are away, somehow. And having contrived this scenario, Vermeer quite often labours to let us know that he has, in fact, staged it. In The Love Letter, the woman and her maid are framed by a doorway, where a curtain is thrown theatrically back to let us in. In Allegory of the Catholic Faith, another curtain reveals what looks more than anything like a woman posing for an allegory painting. In The Milkmaid he leaves, in plain view on the bare whitewashed wall and visible from ten yards, the black pinprick of his perspective guide, which as an essay in the catalogue notes, he can hardly have needed for such a simple scene. Finally, in The Art of Painting, Vermeer shows the painter himself seated, looking on carefully at a woman in an improbable hat, who is herself gazing absentmindedly down, posed clutching an unlikely series of objects.

Mistress and Maid. Oil on canvas, c. 1667.

If these scenes are deliberately conceived, it begs the question: why these scenes in particular? Why these moments of sudden interruption or self-interruption? What thought has led the geographer to look up from his work, his expression a mask of unobservant focus? Why use that same expression of unselfconscious absorption on the faces of both figures in Mistress and Maid? For a comparison, consider a painting by Pieter de Hooch, Vermeer’s Delft contemporary: A Woman Peeling Apples, which hangs in London’s Wallace Collection.

A Woman Peeling Apples, Pieter de Hooch. Oil on canvas, c. 1663.

The painting’s extraordinarily sensitive portrayal of light dissipating into a blue shimmer on the plaster wall led nineteenth century scholars to attribute it to Vermeer himself. I could almost believe it, and having spent many hours standing in front of it I can attest to its powers of enchantment. Yet the sense of time, the painting’s moment and its understanding of that moment, is too broad and sequential for Vermeer. We understand the peeling of the apples as a repeated, soothing, seasonal action; the light entering the room is unmistakeably the light of the early autumn (the apples suggests this too); the clothes worn by the child would have been newly bought, or made for the coming winter, and outgrown by the next autumn; even the light is disintegrating, passing from its status as a thin, pure vertical strip at the window crack into a mottled prismatic blue. This isn’t optics, it’s narrative. The conscious centre of the painting, we feel, is the child, and the sense of cyclical transience that it relays feels, very strongly, as though it comes from that child’s memory. We are looking at something we know we will look back on, and the streaming sunlight itself has the quality of light remembered.

Compare this with what we see in the London National Gallery’s Lady Seated at a Virginal.

Lady Seated at a Virginal. Oil on canvas, c. 1670-72.

The painting is first of all unusually dim for Vermeer. The light is shut out by a blue curtain; another curtain at the top left stages the scene, with its diagonal balanced at the bottom left by a leaning bass viol. On the virginal’s inside lid and the back wall are paintings that are pointedly unlike the one we are looking at. The young woman is just about to play a chord (or has just played one), but has become aware of another point of view. The viewer? The painter? A visitor? A mother, a suitor or disapproving relative? There is a sense of masked confrontation here. Her profoundly ambiguous expression apprises us at a glance, even as it distracts her from her playing. Vermeer has taken immense care to lay out the timescale of this moment, its specific position in time. It is laid thinly between a thousand other similar moments, like a card in an ordered deck. Nothing could be further from de Hooch’s evocations of seasonal return and human memory. Another difference, and an important one, is that this is a drama of perspective. Lady Seated at a Virginal is animated by an awareness of who sees what. The painting knows which points of view are and are not available. The stakes of visibility, enclosure and propriety are heightened by the explicit privacy of a drawn curtain. Where de Hooch is straining to evoke the interior sense of a world seen, Vermeer creates a profoundly exterior painting, one that forces us to confront the limits of what we can see and know. The representation of these limits fascinates Vermeer. Is there a more beautiful example in painting of the unknowable being frankly disclosed than Girl with a Pearl Earring?

This sense—of points of view other than the one we are seeing, the sense of the world as multi-dimensional space viewable from every angle—is always pressing at the edges of Vermeer’s mature work. In Woman with a Pearl Necklace, traditionally read as a parable of vanity, there is that same sense of self-absence in the figure’s concentration. She is looking intently at her reflection, but she is not seeing everything. Vermeer outlines against the wall a piece of thread, trailing at the back of her hair: her precise blind spot. What’s more, she is standing right by the open window, visible to anyone who passes by—and what is a window if not a frame like Vermeer’s, one that shows us just a moment of a domestic scene we cannot fully understand?

Woman with a Pearl Necklace. Oil on canvas, c. 1664.

Here even the highlights on the foregrounded chair and water jug have a Cheshire Cat quality to them. Posing the woman as he does, Vermeer reminds us they are not the highlights, but our highlights. He stresses, through his composed anti-composition, the world’s total and constant presence in space, its unblinking solid reality, and holds this against the contingency of vision. Each room we enter, he seems to say, is full of highlights, perspectives, shadows and standpoints that we cannot see. It is a thoroughgoing materialism, religiously inflected, and it holds that a tree falling in a wood makes a sound regardless of whether anyone is around to hear it. In Richard Wilbur’s poem ‘The Reader’, he makes reference to seeing people’s ‘first and final selves at once / As a God might, to whom all time is now.’ To Vermeer’s God, all space is here, and the total detail of every possible view is ever present.

At the very heart of Vermeer’s painting is the difference between the created world and the world that is seen. In Woman with a Glass of Wine, the fine crack of light between the window casing and the world behind it is a sort of optical pun on the difference, or lack thereof, between light and highlight. Even as her wineglass masks her face, the two highlights on its curved surface shoot out from directly in front of eyes like illustrations of the act of vision. If he used a camera obscura, what it would have taught him was not precision but a heightened awareness of his blindness. While the moving eye brings whatever it fixes on into focus, a camera obscura can fix on only one thing at once, and leaves large portions of the world as an unfocused blur. We can use it to look at the unknown unknowns of the visual field: the unfocused, ever-present parts of our sight we can never focus on.

Vermeer reproduces this limitation of the eye in his canvases, leaving large portions of the background in soft focus. And his famous details are not fine and photographic, as they seem in reproduction. They are the roughest parts of his handling: textured, thickly applied paint that then catches the light of whatever room the painting hangs in. In the lacemaker, the tentacled thread the sitter works from is spooled out in thick, noodly strips like a painting of paint itself. These are not representations of highlights, they are just highlights full stop. Vermeer doesn’t paint the figures of things, he paints their light value. Perhaps this is why he takes such pains to pair fabrics, textures and materials within his already limited vocabulary, pointing out that the bread and the bread basket both bear the roughness of their own making, or that the seeing eye and the blind pearl earring give back light in precisely the same way. In material terms he asks: what is this world actually made of? Extended theologically, the question is simply: who made this world? Yet as the lacemaker’s materials remind us, we already know the answer to that question. This world we are looking at is made of paint. We know the answer to the second question too.